What a treat! Just back from Tel Aviv (see here, here and here), Bauhaus buildings capital of the world, only to find the Barbican mounting a major Bauhaus exhibition. The focus of the exhibition is the work of the Bauhaus school itself, tracing its development and migration from Weimar in 1919, to Dessau and then Berlin before eventual closure in August 1933.

|

| "Bauhaus stage, the building as a stage" Photograph by T. Lux Feiniger, 1929 |

Bauhaus literally means "house of building" and although the first Bauhaus School in Weimar lacked an architectural faculty, its founder was leading architect Walter Gropius . The underlying philosophy of the movement throughout its short life was the creation of a total work of art, in which all arts and architecture would be brought together - a concept similar to that of the Amsterdam School in the Netherlands.

Gropius claimed that the Bauhaus was apolitical but from the beginning it attracted many left wing students, which partly led to its demise in 1933 and the Nazis declaring it "un-German". During its time in Weimar, the school was generously funded by the state government of Thuringia as part of the post First World War effort of making Germany economically competitive - training artists in new techniques to produce high quality goods for export. This source of funding was under constant political pressure from the governing Socialists but in 1924, the Nationalists came to power in Thuringia, halved the budget and introduced temporary contracts which led to the closure in 1925 and relocation to Dessau. Communist Hannes Mayer took over the directorship in 1928 and interestingly helped the school to move into profit for the first time. A radical constructivist he had little time for the aesthetic elements in the school and forced the resignations of long time lecturers including Marcel Breuer and Herbert Bayer - whose work still sells worldwide today. He went on to quarrel with and was dismissed by Gropius in 1930.

Berlin was the third and final home of the school from 1930-33. Several left wing students left in support of Mayer following him to the Soviet Union but the school remained under constant pressure from the growing Nazi movement and when it finally came to power in 1933 the school closed. The director for the last three years of the school's existence was architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Like many before him, he too moved abroad, settling in the United States although this did not prevent him from submitting designs for bridges to be built by the Todt organisation during the early years of his exile.

"Art as life" is big, beautiful and beguiling. It includes examples of painting, theatrical design, toys and games, graphics, photography, fabrics and all of the other products designed in this short but hugely significant and still influential period. With so much to see, its difficult to take everything in during one visit, so I will concentrate on a few favourite items.

|

| The Studio Window, Lyonel Feininger, 1919 |

The exhibition starts on the upper level of the gallery. The first room includes Lyonel Feininger's oil on canvas work "The Studio Window". Painted in 1919 with distinct cubist influences, it shows a dark and forbidding city scene with the only light coming from the "studio window" perhaps indicating the value and potentially enlightening impact of art. Born in New York in 1887 to a German father and an American mother, Feininger was Gropius' first faculty appointment in 1919, becoming head of the printmaking workshop and lecturing for many years. Declared a "degenerate" artist by the Nazis, he fled Germany with his wife in 1936, settling in New York and going on to create many more works until his death in 1956. An early exponent of what is now know as the graphic novel, he was associated with the Berlin Secession in 1909 and later on the Die Brucke and the Blaue Reiter groups, all of which exerted great influence on the development of European expressionist art in particular.

The philosophy of the Bauhaus combined crafts and fine arts, branching out to embrace many different forms and into many different fields. Like many artistic movements of its time, the Bauhaus experimented with theatre. This included costume and set design but probably peaked with the production of Das Triadische Ballet (the Triadic Ballet), a complete dance performance created by Oskar Schlemmer before joining the Bauhaus in 1921, but premiered in Stuttgart in 1922. The piece consists of three sections, the first on a lemon-yellow stage set is described as a serve burlesque; the second on a pink set is festive-carried whilst the third on a black stage set is described as mystical-fantastic. There are three performers, one male and two female and each dance 12 dances.

The uniqueness of Das Triadische Ballet is that the costumes dictate movement rather than the dancer. The heavy, sculptural costumes and masks severely inhibit the dancers' range of motion but at the same time stimulate and introduce new movements. The costumes include metallic elements and can be seen in all their glory in this exhibition. This work reminds me of the dance elements of the constructivist movement in Russia as well as the Ballet of the Palette, referred to in this post about Josef Herman.

|

| Costume for the Turkish dancer, Das Triadische Ballett, Oskar Schlemmer, 1922 |

Still on the subject of theatre, one of my favourite exhibits is the 1924 stage and costume design for "Circus" by Xanti Schawinsky. Swiss born Schawinsky was an accomplished designer, photographer and member of the Bauhaus jazz band. He left Berlin in 1933 for Milan and worked on iconic poster designs for Cinzano and Olivetti amongst others. "Circus" is a simple, childlike image of an asymmetrical ringmaster/ mistress leading a lion in a dance set against a solid black background. Displayed adjacent to puppets and toys designed by Bauhaus members, I like the ambiguity of the ringmaster/ mistress and the childlike innocence of the friendly but fierce looking lion.

|

| Circus, Xanti Scawinsky, 1924 |

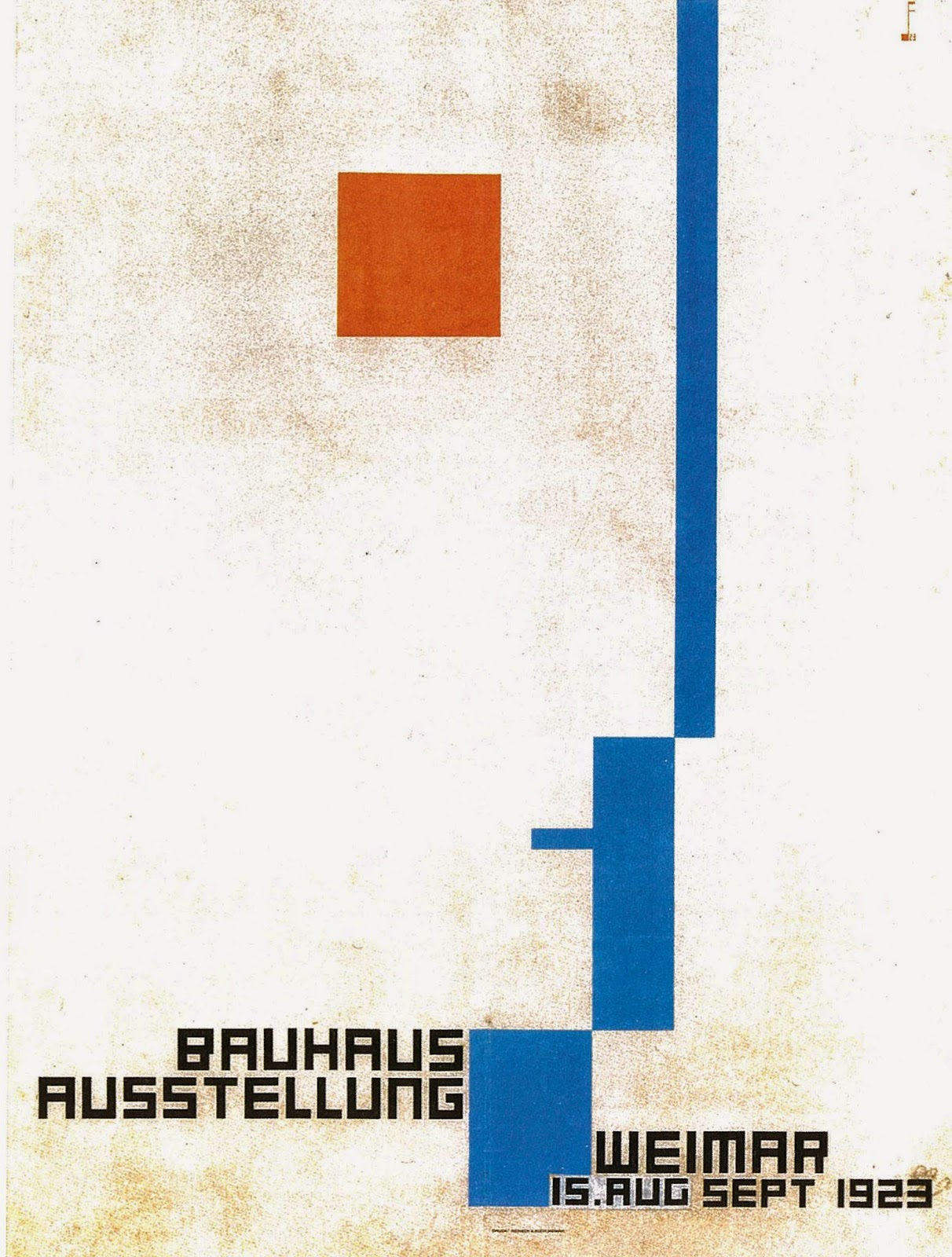

In 1923, under the direction of Gropius, the school staged a major exhibition to demonstrate what Thuringia was getting for its money. The Barbican exhibition has several items from the 1923 event, including some wonderful promotional items such as Fritz Scheliefer's ultra modernist poster and a series of postcards by Herbert Bayer. The exhibition included painting, interior design, performances of the Triadische Ballet, architectural designs and plans as well as toys and games for children. The exhibition is credited with ensuring the continuation of the school as well as introducing its work to a mass audience. Gropius himself gave a keynote speech on the subject of "Art and technology: a new unit" further demonstrating his belief in the total work of art but one constructed using modern techniques.

|

| Poster for the 1923 Bauhaus exhibition, Fritz Schleifer, 1923 |

I am particularly drawn to graphic design of the 1930's and the Bauhaus movement made a major contribution to this discipline with the work of Herbert Bayer being particularly significant. Austrian Bayer had been trained in the art nouveau style, but became interested in Gropius' manifesto and studied at the Bauhaus for four years before being appointed to direct the printing and advertising workshop opened at the new Dessau location. In 1925 Gropius commissioned him to design a house typeface for all Bauhaus communication which resulted in the simple, geometric sans-serif "universal" font.

Bayer developed his own philosophy for type design based on three fundamental principles - that typography is shaped by functional requirements; that the aim of typographic layout is communication and is most effective in its shortest and simplest form, and that for it to serve social ends, typography must have both ordered content and be properly related. Bayer's approach to simplicity included a belief that there was no need for upper and lower case letters, interestingly something that has been revived in 21st century advertising and communications.

The exhibition carries some great examples of Bayer's work. I love his "Design for a cigarette pavilion" and "Design for a news kiosk". Both are thrilling with vibrant colour, the former using a cigarette as a chimney on the roof of the matchbox or cigarette packet pavilion and the latter playing similar tricks with newspapers. The cigarette pavilion image is still widely in demand in poster format almost 90 years after it was designed. Equally inspiring and modern looking are Bayer's catalogues and sales brochures for a range of Bauhaus and other products.

|

| Design for a cigarette pavilion, Herbert Bayer, 1924 |

One time art director at Vogue's Berlin office, Bayer remained in Germany for longer than many of his Bauhaus colleagues after the closure of the school, even designing a brochure for use at the 1936 Olympics extolling the virtues of life in the Third Reich and the authority of Hitler. This didn't save him from being included in an exhibition of "degenerate art" in 1937 which provoked his flight to Italy and then to the USA in 1938.

Which leads us to the troubled relationship between the Bauhaus School and the Nazi state. The school was considered subversive by the Nazis and eventually closed because of this but not before the final head of school, Mies van der Rohe had attempted to bargain with the regime in order to continue. To his credit he refused to agree to their conditions and closed the school himself. This ambiguous relationship is reflected in the experiences of individual Bauhaus artists. Franz Ehrlich had strong communist sympathies and was sent to Buchenwald in 1937. Released in 1939 he worked for the new regime as part of the conditions of release and was even involved in the design of the Sachsenhausen camp. At the same time there is anecdotal evidence that he was also involved in resistance work.

For others there was no ambiguity. Graphic designer Kurt Kranz did design work for the Todt company that benefited from mass slave labour during this period and Herman Gretsch, crockery and tableware designer was a fully signed up member of the Nazi party and worked throughout the war.

Jewish artists Otti Berger and Friedl Dicker-Brandeis worked in the weaving workshops. No ambiguity for them, they were both murdered at Auschwitz. Other Jewish artists fled whilst they still could include Marcel Breuer, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Anni Albers, Nahum Slutsky and Xanti Schawinsky. Other "German" artists, including iconic lamp designer Wilhelm Wagenfeld remained in Germany and later expressed regret for not having done more to resist. At least they had the option of regret.

A great exhibition, but I have a few quibbles. It was a bit poor that at the first weekend the Barbican wasn't able to offer the full range of merchandise associated with the exhibition and had to resort to taking names and numbers to let people know when items arrive. Chaos in the cloakroom, not because of the staff, but because its too small to cope with so many people - but then I suppose they could have expected less coats in May!

The catalogue is excellent and contains several thought provoking and enlightening articles, but can we get one very important thing right? The foreword refers to a period "after the National Socialists seized power". Let's be clear - there was no "seizure" of power. They were elected. Germans voted for them in their millions. Re-writing history does no-one any favours and its not something that would have been difficult to get right.

One wonders what achievements the school might have made had it continued in a different environment. It is possible to see what those results might have been in many of the products people buy from design stores today which clearly show Bauhaus influences, whilst in the streets of Tel Aviv we can see what many European cities might have looked like if things had turned out differently.

|

| The Bauhaus Band (from the top, Oskar Schlemmer, Werner Jackson, Xanti Schawinsky, Clemens Roseler). Photograph by T. Lux Feininger, c1928. |

No comments:

Post a Comment